- Home

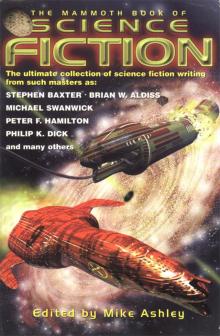

- Mike Ashley (Editor)

The Mammoth Book Of Science Fiction Page 3

The Mammoth Book Of Science Fiction Read online

Page 3

McCarthy: “It’s all hazy, Enright. Can’t see much.”

Enright stood, tested his limbs. He was fine. No breaks. He stepped forward, out of the direct sunlight, and stared at the ranked machinery that disappeared into the perspective.

“Hell fire in heaven!” Jeffries murmured.

Spirek was still peering down at him, unsure whether to negotiate the landslide.

“Ed, are you gonna tell me?”

He peered up at her. “Get yourself down here, Sal.”

She hesitated, then stepped forward and rode the sliding sand down to him like a kid on a dune.

She lost her footing and sprawled on her back. Enright helped her up. He was still holding her hand, staring past her face plate to watch her expression, as she turned and looked down the length of the chamber.

She said nothing, but silver tears welled in her eyes.

Then, without a word, spontaneously, they embraced.

Hand in hand, like frightened kids, they walked down the chamber.

They approached the machinery, the craft, rather. There were dozens of them, each one tall and columnar and bulky. They were dark shapes, seemingly oiled, silent and static and yet, every one upright and aimed, seemingly poised with intent.

Then they came to a smaller piece of machinery, perhaps half the height of the columns. Enright stopped, and stared.

He could not help himself: he began weeping.

“Ed?” Sal said, gripping his hand in sudden fear.

He indicated the looming, legged, vehicle.

She shook her head. “So what? I don’t see . . . ?”

In his head-set, Enright heard McCarthy, “Hey, you two oughtta be heading back now. Sal, how much air you got there?”

Sal swore. “Dammit, Ed. We gotta be getting back.”

He was staring at the vehicle, mesmerised. “Ed!” Sal called again.

Reluctantly, Enright turned and followed Sal back up the landslide to the Marsmobile.

England, in contrast to sun-soaked Florida, was caught in the grip of its fiercest winter for years. From the window seat of the plane as it came in to land, Enright stared down at a landscape sealed in an otherworldly radiance of snow. This was the first time he had seen snow for almost twenty years, and he thought the effect cleansing: it gave mundane terrain a transformed appearance, bright and pristine: it looked like a land where miracles might easily occur.

He caught a Southern Line train from Heathrow to the village of Barton Humble in Dorset, and from there a taxi to Brimscombe Manor.

For the duration of the ten mile drive, Enright stared out at a landscape every bit as alien and fascinating as the terrain of Mars. He seemed to be travelling deep into the heart of ancient countryside: everything about England, he noted, possessed a quality of age, of history and permanence, entirely lacking in the American environment to which he was accustomed. The lanes were deep and rutted, with high hedges, more suited to bullock-carts than automobiles. They passed an ancient forest of oak, the dark, winter-stark trees bearing ghostly doppelgangers of themselves in the burden of snow that limned every branch.

Brimscombe Manor, when it finally appeared, standing between the forest and a shallow rise of hills, was vast and sprawling, possessed of a tumbledown gentility that put Enright in mind of fading country houses in the quaint black and white British films he’d watched as a child.

The driver took one look at the foot-thick mantle of snow that covered the drive of the Manor, and shook his head. “Okay if I drop you here?”

Enright paid him off with unfamiliar European currency, retrieved his bag from the back seat, and stood staring at the imposing façade of the Manor as the taxi drove away.

He felt suddenly alone in the alien environment. He knew the sensation well. The last time he had experienced this gut-wrenching sense of dislocation, he had been on Mars.

What the hell, he wondered, am I doing here? He had the sudden vision of himself, a US astronaut, standing forlornly in the depths of the English countryside on a freezing December afternoon, and smiled to himself.

“Ulla, ulla,” he said, and his breath plumed in the icy air before him, the effect at once novel and disconcerting. “I’m going mad.”

He set off through the snow. His boots compacted ice crystals in a series of tight, musical squeaks.

A light burned, orange and inviting, behind a mullioned window in the west wing of the Manor. He climbed a sweep of steps and found a bell-push beside the vast timber door.

Thirty seconds later the door swung open, and heat and light flooded out to greet him.

“Mr Enright, Ed, you can’t imagine how delighted I am . . .”

Within seconds of setting eyes upon his long-term correspondent, Enright felt at ease. Connaught had the kind of open, amicable face that Enright associated with English character actors of the old school: he guessed Connaught was in his early sixties, medium height, a full head of grey hair, wide smiling mouth and blue eyes.

He wore tweeds, and a waistcoat with a fob watch on a silver chain.

“You must be exhausted after the journey. It’s appalling out there.” He escorted Enright across the hall. “Ten below all week. Record, so I’m told. Coldest cold snap for sixty years. You’ll want a drink, and then dinner. I’ll show you to your room. As soon as you’ve refreshed yourself, join me in the library.”

He indicated a room to the right, through an open door. Enright glimpsed a roaring open fire and rank upon rank of books. “This is the library, and right next door is your room. I hope you don’t mind sleeping on the ground floor. I live here alone now, and since Liz passed away I don’t bother with the upstairs rooms. Cheaper just to live down here. Here we are.”

He showed Enright into a room with a double bed and an en suite bathroom, then excused himself and left.

Enright sat on the bed, staring through the window at the snow-covered lawn and the drive. The only blemish in the snow was his footprints, which a fresh fall was already filling in.

He showered, changed, and ventured next door to the library.

Connaught stood beside a trolley of drinks. “Scotch, Brandy?”

He accepted a brandy and sat on a leather settee before the open fire. Connaught sat to the right of the fire in a big, high-backed leather armchair.

He surprised himself by falling into a polite exchange of Smalltalk. His curiosity was such that all he wanted from Connaught was an explanation of the letter which he carried, folded, in his hip pocket.

Ulla, ulla . . .

He fitted sound-bites and observations around Connaught’s questions and comments.

“The flight was fine – a tailwind pushed us all the way, cutting an hour and a half off the expected time . . .

“England surprises me . . . Everything seems so old, and small . . .

“I’m impressed by the Manor . . . We don’t have anything quite like this back home.”

And then they were discussing the history of manned space exploration. Connaught was extremely knowledgeable, indeed more so than Enright, in his grasp of the political cut and thrust of the space race.

An hour had elapsed in pleasant conversation, and still he had not broached the reason for his visit.

Connaught glanced at the carriage clock on the mantelshelf. “Eight already! Let’s continue the conversation over dinner, shall we?”

He ushered Enright along the hall and into a comfortable lounge with a table, laid for two, in a recessed area by the window.

A steaming casserole dish, a bowl of vegetables, and a bottle of opened wine, stood on the table.

Connaught gestured to a seat. “I hire a woman from the village,” he explained. “Heavenly cook. Comes in for a couple of hours a day and does for me.”

They ate. Steak and kidney casserole, roast potatoes, carrots and asparagus. They finished off the first bottle and started into a second.

The night progressed. Enright relaxed, drank more wine.

The amicable tenor

of their correspondence was maintained, he was delighted to find, in their conversation. He contrasted the humane Connaught with the bullish egomania of McCarthy.

Ulla, ulla . . .

Suddenly, the conversation switched – and it was Connaught who instigated the change.

“Of course, I watched every second of the Mars coverage. I was glued to the Net. I hoped and prayed that your team might discover something there, though of course I was prepared for disappointment . . . I’ll tell you something, Ed. I harboured the desire to be an astronaut myself, when I was young. Just a dream, of course. Never did anything about it. I fantasised about discovering new worlds, alien civilizations.”

Enright smiled. “I never had that kind of ambition. I slipped into the space program almost by accident. They wanted a geologist on the mission, and I volunteered.” He hesitated. “So when I stepped out onto Mars, of course the last thing on my mind was the discovery of an alien civilization.”

“I was watching the cast when you fell. The moment you said those words, I knew. Your tone of disbelieving wonder told me. I just knew you’d found something.”

Connaught refilled the glasses. “What happened, Ed? Tell me in your own words how you came to . . .”

So he recounted the landing, his first walk on the surface of Mars, and then his second. He worked up to his fall, and the discovery, like an expert storyteller. He found he was enjoying his role of raconteur . . .

They arrived back at the lander, after the discovery, with just four minutes’ air supply remaining.

McCarthy and Jeffries were standing in the living quarters when they cycled through the hatch and discarded their suits. They were white-faced and silent.

Enright looked around the group, shaking his head. Words, at this moment, seemed beyond him.

McCarthy said, “Mission control went ballistic. You should hear Roberts. Wait till this breaks!”

Sal Spirek slumped into a seat. “We’re famous, gentlemen. I think that this just might be the most momentous occasion in the history of humankind, or am I exaggerating?”

They stared around at each other, trying to work out if indeed she was exaggerating.

Enright was shaking his head.

“What is it?” Sal asked.

He could not find the words to articulate what even he found hard to believe. “You don’t understand,” he began.

Sal said, “What’s wrong?”

“Those things back there,” Enright said, “the cylindrical rockets and three-legged machines.” He stared around at their uncomprehending faces. “Have none of you ever read The War of the Worlds?”

Six hours later, with the go ahead of Roberts at mission control, all four astronauts suited up and rode the Mars-mobile to the subterranean chamber.

As he negotiated the sloping drift of red sand, Enright half-expected to find the cavern empty, the cylinders and striding machines revealed to be nothing other than a figment of his imagination.

He paused at the foot of the drift, Sal by his side, McCarthy and Jeffries bringing up the rear and gasping as they stared at the alien machinery diminishing in perspective.

He and Sal walked side by side down the length of the chamber, passing from bright sunlight into shadow. He switched on his shoulder-mounted flashlight and stared at the vast, cylindrical rockets arrayed along the chamber. They were mounted on a complex series of frames, and canted at an angle of a few degrees from the perpendicular.

They paused before a smaller machine, consisting of a cowled dome atop three long, multi-jointed legs.

McCarthy and Jeffries joined them.

“Fighting Machines,” Enright said.

McCarthy looked at him. “Say again?”

“Wells called them Fighting Machines,” he said. “In his book –”

He stopped, then, as the implications of what he was saying slowly dawned on him.

He walked on, down the aisle between the examples of an alien culture’s redundant hardware. The atmosphere within the chamber was that of a museum, or a mausoleum.

McCarthy was by his side. “You really expect us to believe . . . ?” he began.

Spirek said, “I’ve read The War of the Worlds, McCarthy. Christ, but Wells got it right. The cylinders, the Fighting Machines . . .”

“That’s impossible!”

Enright said, “It’s all here, McCarthy. Just as Wells described it.”

McCarthy looked at him, his expression lost in the shadow behind his faceplate. “How do you explain it, Enright?”

He shrugged. “I don’t. I can’t. God knows.”

“Here!” Spirek had moved off, and was kneeling beside something in the shadow of a tripod.

“The hardware wasn’t all Wells got right.” She gestured. “Look . . .”

Mummified in the airless vault for who knew how long, the Martian was much as the Victorian writer had described them in his novel of alien invasion, one hundred and twenty years before.

It was all head, with two vast, dull eyes the size of saucers, and a beak, with tentacles below that – tentacles that Wells had speculated the aliens had walked upon. It was, Enright thought, more hideous than anything he had ever seen before.

Enright walked on, and found more and more of the dead aliens scattered about the chamber.

Jeffries said, “I’ll get all this back to Roberts. We need to work out strategy.”

Enright looked at him. “Strategy?”

Jeffries gestured around him. “This is a security risk, Enright. I’m talking an Al security risk, here. How do we know these monsters aren’t planning an invasion right now? Isn’t that what the book was about?”

Enright and Spirek exchanged a glance.

“The Martians are dead, Jeffries. Their planet was dying. They lived underground, but air and food was running out. They died out before they could get away.”

“You don’t know that, Enright. You’re speculating.”

Enright strode off. He needed isolation in which to consider his discovery.

He found other chambers through giant archways, and a series of ramps that gave access to even lower levels. He imagined an entire city down there, a vast underground civilization, long dead.

Sal Spirek joined him. “How did Wells know?” she asked. “How could he possibly have known?”

Enright recalled the last time he had read the novel, in his teens. He had been haunted by the description of a ravaged, desolate London in the aftermath of the alien invasion. He recalled the cry of the Martians as they succumbed to a deadly Terran virus, the mournful lament that had echoed eerily across an otherwise deathly silent London. “Ulla, ulla, ulla, ulla . . .”

“What was it like when I looked upon those ranked machines?” Enright shook his head. “I felt more than I thought, Joshua. I was overwhelmed with disbelief, and then elation, and then later, back at the ship, when I thought about it, a little fear. But at the time, when I first saw the machines . . . it came as one hell of a shock when I realized why they were so familiar.”

Connaught was nodding. “Wells,” he said.

Enright let the silence stretch. “How did you know?” He leaned forward. “How did Wells know?”

Connaught stood. “How about a whiskey? I have some fine Irish here.”

He moved across the room to a mahogany cabinet and poured two generous measures of Bushmills.

He returned to the table. Enright sipped his drink, feeling the mellow burn slide down his throat like hot velvet.

“My great-grandfather, James,” Connaught said, “inherited the Manor from his father, who built the Manor in 1870 from profits made in the wine trade. James was a writer – unsuccessful and unpublished. He wrote what was known then as scientific romances. He self-published a couple of short books, to no great notice. To be honest, his imagination was his strong point – his literary ability was almost negligible. To cut a long story short, he was friendly with a young and aspiring writer at the time – this was around the 1890s. Chappie b

y the name of Wells. They spent many a weekend down here and swapped stories, ideas, plots, etc . . . One story James told him was about the invasion of Earth by creatures from Mars. They came in vast cylinders, and stalked the earth aboard great marching war machines. Apparently, my great-grandfather had tried to write it up himself, but didn’t get very far. Wells took the idea, and the rest is history. The War of the Worlds. A classic.”

Connaught paused, staring into his glass.

Enright nodded, his mind full of H.G. Wells and James Connaught discussing story ideas in this very building, all those years ago.

“How,” he asked at last, “how did your great-grandfather know about the Martians?”

He realized that he was drunk, his speech slurred. The sense of anticipation he felt swelling within him was almost unbearable.

“One night way back in 1880,” Connaught said, “James was out walking the grounds. This was late, around midnight. He often took a turn around the garden at this time, looking for inspiration. Anyway, he saw something in the sky, something huge and fiery, coming in from the direction of the coast. It landed with a loud explosion in the spinney to the rear of the Manor.”

Enright leaned forward, reached for the whiskey bottle, and helped himself.

“James ran into the spinney,” Connaught continued, “after the fallen object, and found there . . . He found a huge pit gouged into the ground, and in that pit a great cylindrical object, glowing red and steaming in the cold night.”

Enright sat back in his chair and shook his head.

Joshua Connaught smiled. “You don’t believe me?”

“No, it’s just . . . I do believe you. It’s just that it’s so fantastic . . .”

Connaught said, “My great-grandfather excavated the pit and built an enclosure around it, and it exists to this day. I’ve shown no one since Elizabeth.”

Enright experienced a sudden dizziness. He made a feeble gesture.

Connaught smiled. “It’s still there, Ed.”

Enright shook his head. “It, you mean . . . ?”

“The Martian cylinder, and other things.”

The Mammoth Book Of Science Fiction

The Mammoth Book Of Science Fiction